On 1 September, 80 years ago last month, Adolf Hitler’s Nazi legions invaded Poland to start World War II; a war that was to prove the deadliest and the most destructive war in human history. It marked the day when Europe finally committed suicide. Eighty years on, world leaders convened in Warsaw to mark and remember that terrible moment in history.

On 1 September, 80 years ago last month, Adolf Hitler’s Nazi legions invaded Poland to start World War II; a war that was to prove the deadliest and the most destructive war in human history. It marked the day when Europe finally committed suicide. Eighty years on, world leaders convened in Warsaw to mark and remember that terrible moment in history.

World War II lasted from 1939 to 1945 and involved 30 countries from every part of the globe. The war killed an estimated 70-80 million people, or 4 per cent of the world’s population. If war is about breaking things and hurting people, then World War II’s impact was horrific. Soldiers and civilians alike were slaughtered; huge tracts of Europe and western Russia were devastated, with whole cities razed; South East Asia was wracked by war; millions starved; Jews and undesirables were murdered on an industrial scale by the Nazis; and the use of atomic bombs on Japan signalled a new and deadly way of wiping out humanity.

The facts are terrifying. The Soviet Union suffered most, with over 20 million killed. Almost 3.5 million Soviet prisoners of war died in German slave labour camps. German soldiers were ordered to exterminate all Jews, communist leaders, as well as any Soviet civilians resisting the Aryan ‘Master Race’ in order to take their grain and livestock. During the two-year siege of Leningrad, more than 1 million residents starved to death.

Germany fared little better. It lost around 9 million people: 5.3 million soldiers; and 3.3 million civilians. The Nazis murdered 300,000 of their own citizens and the Allied bomber offensive killed 600,000, leaving Germany as a heap of rubble by 1945.

Poland lost 5 million people: 16 per cent of its total population. Of those, 2.7 million were Jews, and 240,000 were soldiers. Yugoslavia lost 1 million people including 445,000 soldiers. France lost 568,000 people, of which 218,000 were soldiers. The United Kingdom lost 60,000 civilians to German air raids and 384,000 military. The United States lost 405,000 soldiers.

Further afield, the war killed 30 million in the Pacific. China lost 20 million, 80 per cent of whom were civilians. In just one incident, the 1937 Nanking massacre, Japan killed around 300,000 Chinese.

Japan’s brutal Samurai Code (‘the way of the warrior’) led to 6 million deaths in China, Japan, Korea, Indochina and the Philippines. This included the slaughter of civilians in villages, slave labour in Korea and China, and the use of human experiments to develop biological weapons. In addition, up to 400,000 ‘comfort women’ were forced into sexual slavery; 90 per cent of these unfortunate females had died by the end of the war.

This lengthy litany of horrifying statistics is vital because they rub home the key point, all too easily forgotten as memory turns to history: Hitler’s war was nothing less than the biggest disaster in recorded history.

The irony is that the war should have come as no surprise. Hitler had, years before, spelled out in cold print his plans for a war to end wars.

As he held court in 1924 as a prisoner in Bavaria’s Landsberg Castle for leading an attempted coup in Munich, Hitler committed his plans to paper. In a turgid and badly written book called Mein Kampf (My Struggle, in English), Germany’s future Führer drafted his battle plan. Germany would rise again and seize by force lebensraum (‘living space’) and raw materials to the east. The malign megalomaniac who caused World War II openly warned the world what he intended to do.

As he held court in 1924 as a prisoner in Bavaria’s Landsberg Castle for leading an attempted coup in Munich, Hitler committed his plans to paper. In a turgid and badly written book called Mein Kampf (My Struggle, in English), Germany’s future Führer drafted his battle plan. Germany would rise again and seize by force lebensraum (‘living space’) and raw materials to the east. The malign megalomaniac who caused World War II openly warned the world what he intended to do.

The problem really started in 1914, when the great powers of Europe blundered into a cataclysmic European civil war, thanks to a system of unwise military alliances and epic diplomatic miscalculation. By 1918, exhausted and bankrupt, the old ‘Europe’ had fallen apart. Four empires lay in ruins: Germany; Austro-Hungary; Russia; and the Ottoman-Turks. Out of the ruins the Peace Treaty of Versailles made things worse.

Versailles imposed savage terms on Germany, holding Berlin responsible for the whole war and demanding unheard of sums as reparations. The German Weimar government printed money to meet its exorbitant payments, thus creating hyperinflation: a wheelbarrow full of millions of Reichsmarks was needed to buy a loaf of bread.

As Germans lost buying power, they looked for salvation. The harsh economic conditions made people turn to new leaders, principally the Communists and the Fascists. Adolf Hitler, a spellbinding orator and embittered veteran of the trenches played on ordinary Germans’ fears. Leading his National Socialist Party, he blamed the Jews for Germany’s defeat and promised a return to power, full employment and prosperity. A generation of Germans welcomed his policies and his promise to make Germany great again.

Once again, nationalism was on the rise. In Germany, Mussolini’s Italy and Japan’s warrior state, new leaders advocated militarism, re-armament and the use of naked force to overcome other nations and seize their natural resources.

In 1931 Japan struck. The island nation required oil and food imports to feed its growing population. In what many consider to be the true start of World War II, Japan invaded China, intent on grabbing the mineral riches of Manchuria. The powder train to a wider war was burning, because the global economy was in crisis; the Wall Street Crash of 1929-31 changed everything.

The Great Depression and economic crisis reduced global trade by 25 per cent. In Germany, unemployment reached 30 per cent. Communism began to look attractive to the millions of unemployed and broke. To quell rioting on the streets, Germany’s politicians and industrialists turned to Hitler and his Nazi Party as a bulwark against this growing ideological threat from the east.

On 30 January 1933 they appointed him Chancellor. It was a grave mistake.

On 30 January 1933 they appointed him Chancellor. It was a grave mistake.

Within months Hitler and his henchmen had seized full power. Following a disastrous fire at the Reichstag – almost certainly ignited by the Nazis – President Hindenburg published a decree on 28 February 1933 as an emergency response to what was widely believed to be a Communist Coup. It suspended many of the civil liberties of German citizens. It was swiftly followed by an ‘Enabling Act’ on 23 March 1933, as ‘A Law to Remedy the Distress of People and Reich’, an amendment to the Weimar Constitution. It gave the Chancellor power to enact laws without the involvement of the Reichstag.

Hitler was now the legal dictator of Germany. With all power in his hands his plan for a war of conquest was now possible.

The rest, as they say, is history. Hitler, now ‘Supreme Leader’ of the Germans, tore up the Versailles Treaty, re-armed Germany and began his long European land grab for the Rhineland, Austria, Czechoslovakia and then Poland.

Finally Hitler did two things in that final summer of 1939 to make sure that no one stood in his way.

Finally Hitler did two things in that final summer of 1939 to make sure that no one stood in his way.

On 23 July, to the amazement of the world, Ribbentrop and Molotov signed a formal ‘Non-Aggression Pact’ between the two sworn ideological enemies. Unbelievably, Hitler’s Nazi Germany and Stalin’s Communist USSR were now allies.

Hitler’s final step towards the war he had dreamed about and planned for in Landsberg fortress was a typical deceit. Rather than openly declare war, he resorted to trickery.

Hitler’s final step towards the war he had dreamed about and planned for in Landsberg fortress was a typical deceit. Rather than openly declare war, he resorted to trickery.

On the eve of that fateful day – 31 August 1939 – a handful of doomed concentration camp prisoners were given Polish uniforms, unloaded rifles and ordered to attack an isolated German frontier post on the Polish border. The Wehrmacht machine gunners at Gleiwitz were waiting. The wretched prisoners were slaughtered to a man. Journalists were later invited to view the bodies at the scene as Doctor Goebbels’ Nazi propaganda machine swung into action to denounce a Polish atrocity.

At dawn the next day – 1 September 1939 – Hitler’s Panzers and Stukas attacked Poland to seize lebensraum to the East. World War II had begun. It had all been predicted by the Mein Kampf blueprint.

Hitler’s war would complete what 1914-18 had begun: the destruction of Europe. From 1945 onwards, America, fat on Europe’s gold and self-immolation, took over the role of world leader.

Curiously, that outcome does not feature in Mein Kampf….

This reflection was first published by John Hughes- Wilson on the Intelligence Corps Association website (on 14 August 2019)

This reflection was first published by John Hughes- Wilson on the Intelligence Corps Association website (on 14 August 2019) I briefed the General and his Chief of Staff, Roger Wheeler, later. They fell about laughing. ‘So much for DI 24 Security.’

I briefed the General and his Chief of Staff, Roger Wheeler, later. They fell about laughing. ‘So much for DI 24 Security.’ Everyone in Cyprus knows that the Turks intervened in Cyprus in July 1974. However, thanks to clever, well-funded and unremitting Greek propaganda, the world has been led to believe that this was nothing less than a brutal and uncalled-for invasion against the peace-loving Greeks – an Ottoman jackboot to seize Greek land and occupy Cyprus.

Everyone in Cyprus knows that the Turks intervened in Cyprus in July 1974. However, thanks to clever, well-funded and unremitting Greek propaganda, the world has been led to believe that this was nothing less than a brutal and uncalled-for invasion against the peace-loving Greeks – an Ottoman jackboot to seize Greek land and occupy Cyprus.

By 14 August the Geneva talks, aimed at a political solution, had broken down. Turkey’s demands for a bi-zonal federal state plus complete population transfer shocked Cyprus’ new acting President Glafcos Clerides, who begged for an adjournment in order to consult Athens and Greek-Cypriot politicians. The long shadow of the Machiavellian archbishop fell over the negotiating table, however. No one trusted Makarios, who was dissembling, lying and stalling to the last.

By 14 August the Geneva talks, aimed at a political solution, had broken down. Turkey’s demands for a bi-zonal federal state plus complete population transfer shocked Cyprus’ new acting President Glafcos Clerides, who begged for an adjournment in order to consult Athens and Greek-Cypriot politicians. The long shadow of the Machiavellian archbishop fell over the negotiating table, however. No one trusted Makarios, who was dissembling, lying and stalling to the last. After three days of continuous advance and confused fighting it was all over. Cyprus was sliced in half. The two communities were ethnically separated. Thousands of refugees were displaced from their homes. The Greek Junta and their puppet Sampson went to jail. The UN’s temporary ceasefire still remains the legal position.

After three days of continuous advance and confused fighting it was all over. Cyprus was sliced in half. The two communities were ethnically separated. Thousands of refugees were displaced from their homes. The Greek Junta and their puppet Sampson went to jail. The UN’s temporary ceasefire still remains the legal position.

August has always been a good month to start a war. The reasons are simple: the harvest is ripening; the men are fit and ready; the long days are perfect for campaigning without worrying about the weather; and the summer heat seems to encourage rash decisions. In the Foreign Legion they call it le cafard – the depression or madness brought on by a hot summer.

August has always been a good month to start a war. The reasons are simple: the harvest is ripening; the men are fit and ready; the long days are perfect for campaigning without worrying about the weather; and the summer heat seems to encourage rash decisions. In the Foreign Legion they call it le cafard – the depression or madness brought on by a hot summer.

The irony is that it all went wrong from the start and could have been avoided with a little adroit diplomacy. If there is a villain of the story in 1914 it was the German General Staff, who had been planning for years how to deal with a war on two fronts. Under the eye of a workaholic general (he even went to work on Christmas day, according to his family), Generaloberst Alfred von Schlieffen devised a plan. Blackadder would probably have it called it ‘a plan so cunning you could stick a tail on it and call it a weasel.’

The irony is that it all went wrong from the start and could have been avoided with a little adroit diplomacy. If there is a villain of the story in 1914 it was the German General Staff, who had been planning for years how to deal with a war on two fronts. Under the eye of a workaholic general (he even went to work on Christmas day, according to his family), Generaloberst Alfred von Schlieffen devised a plan. Blackadder would probably have it called it ‘a plan so cunning you could stick a tail on it and call it a weasel.’ Late in the afternoon of 1 August 1914, Colonel General Helmuth von Möltke was driving back to the Army HQ in the Königsplatz when his car was stopped and he was commanded to return to the Royal Palace immediately. Back at the Berliner Schloss, a jubilant Kaiser told the head of the German armies that he had received a telegram from London assuring him that Britain would guarantee that, if Germany refrained from going to war with France, then London would ask the French not to attack Germany.

Late in the afternoon of 1 August 1914, Colonel General Helmuth von Möltke was driving back to the Army HQ in the Königsplatz when his car was stopped and he was commanded to return to the Royal Palace immediately. Back at the Berliner Schloss, a jubilant Kaiser told the head of the German armies that he had received a telegram from London assuring him that Britain would guarantee that, if Germany refrained from going to war with France, then London would ask the French not to attack Germany. This is where the general staff got it so badly wrong; like a piece of elastic the German supply line was stretched a little further every day. In those pre-lorry days, every round of ammunition, every bale of hay for the horses, every bit of food for the weary troops, even horseshoes and new boots for the footsore soldiers, had to find its way forward on an ever-lengthening supply chain to the advancing armies, which were getting further and further away from their logistic bases.

This is where the general staff got it so badly wrong; like a piece of elastic the German supply line was stretched a little further every day. In those pre-lorry days, every round of ammunition, every bale of hay for the horses, every bit of food for the weary troops, even horseshoes and new boots for the footsore soldiers, had to find its way forward on an ever-lengthening supply chain to the advancing armies, which were getting further and further away from their logistic bases. The row that has blown up over the leaking of the British ambassador’s private opinions of President Trump and his administration has far-reaching consequences.

The row that has blown up over the leaking of the British ambassador’s private opinions of President Trump and his administration has far-reaching consequences. In the late 1770s this was remarkable stuff. Across the Atlantic, radical MP and journalist

In the late 1770s this was remarkable stuff. Across the Atlantic, radical MP and journalist  Early American courts struggled with the argument that the punishment of ‘dangerous or offensive writings… [was] necessary for the preservation of peace and good order…’ How did that balance with a free press guaranteed by federal law? That difficult question was swept under the carpet for two centuries after the ratification of the First Amendment to the US Constitution.

Early American courts struggled with the argument that the punishment of ‘dangerous or offensive writings… [was] necessary for the preservation of peace and good order…’ How did that balance with a free press guaranteed by federal law? That difficult question was swept under the carpet for two centuries after the ratification of the First Amendment to the US Constitution. The Supreme Court agreed, and held that virtually all forms of restraint on free speech were unconstitutional. The key was that embarrassing the government was no crime; the real illegality was the theft of secrets.

The Supreme Court agreed, and held that virtually all forms of restraint on free speech were unconstitutional. The key was that embarrassing the government was no crime; the real illegality was the theft of secrets. The irony is that the British press are often far too ‘responsible’. For example, over the

The irony is that the British press are often far too ‘responsible’. For example, over the  The following letter from John Hughes-Wilson was published in The Telegraph on Saturday, 29 June 2019, in response to an article entitled ‘

The following letter from John Hughes-Wilson was published in The Telegraph on Saturday, 29 June 2019, in response to an article entitled ‘ All five novels in the ‘Tommy Gunn’ World War I ‘Chronicles of the Winter World’ series are now published by Mereo Books.

All five novels in the ‘Tommy Gunn’ World War I ‘Chronicles of the Winter World’ series are now published by Mereo Books. ‘Peace at home; peace in the world.’ Atatürk’s homely ambition has never been more important for Turkey. However, a number of crises are coming together inexorably to force Ankara to think long and hard about its future intentions. Turkey is at a major crossroads.

‘Peace at home; peace in the world.’ Atatürk’s homely ambition has never been more important for Turkey. However, a number of crises are coming together inexorably to force Ankara to think long and hard about its future intentions. Turkey is at a major crossroads. Then, in late June 2019 (in the margins of the G20 Osaka meeting), the Turkish president claimed that a deal had been struck. President Trump had told him there would be no sanctions over the Russian deal and that Turkey had been had been ‘treated unfairly’ over the move.

Then, in late June 2019 (in the margins of the G20 Osaka meeting), the Turkish president claimed that a deal had been struck. President Trump had told him there would be no sanctions over the Russian deal and that Turkey had been had been ‘treated unfairly’ over the move. The problem is that Turkey and Russia have serious form going back to the days of the Tsars. For example, the Crimean War in the 1850s was really all about Russian and Turkish rivalry. Since the days of the Ottoman Empire, Turkey has always sought to deny Russia a significant presence to the south or in the eastern Mediterranean. But that is now where Russia is becoming increasingly active – especially in Syria. As Russian influence grows, Turkey’s room for regional influence shrinks. Turkey’s recent accommodation of Russia is therefore historically and geopolitically unusual.

The problem is that Turkey and Russia have serious form going back to the days of the Tsars. For example, the Crimean War in the 1850s was really all about Russian and Turkish rivalry. Since the days of the Ottoman Empire, Turkey has always sought to deny Russia a significant presence to the south or in the eastern Mediterranean. But that is now where Russia is becoming increasingly active – especially in Syria. As Russian influence grows, Turkey’s room for regional influence shrinks. Turkey’s recent accommodation of Russia is therefore historically and geopolitically unusual. Right! Hands up all those who have heard of rare earths?

Right! Hands up all those who have heard of rare earths? Scandium Found in aerospace alloys and cars’ headlamps

Scandium Found in aerospace alloys and cars’ headlamps So, just as with plastic, the West has ducked responsibility, outsourcing the environmental challenges of rare earths by dumping the problem out in the dusty deserts and cheap mass labour of far-distant China. By doing so it has allowed Beijing to corner the global market. There’s a price; China holds 37 per cent of the world’s rare-earth deposits and it controls the rest. Even when rare earths are mined in the US – or in other nations, such as Estonia – the extracted material is sent to China for processing. It’s cheaper, easier and, most important, it avoids the environmental lobby’s inevitable shrieks of outrage.

So, just as with plastic, the West has ducked responsibility, outsourcing the environmental challenges of rare earths by dumping the problem out in the dusty deserts and cheap mass labour of far-distant China. By doing so it has allowed Beijing to corner the global market. There’s a price; China holds 37 per cent of the world’s rare-earth deposits and it controls the rest. Even when rare earths are mined in the US – or in other nations, such as Estonia – the extracted material is sent to China for processing. It’s cheaper, easier and, most important, it avoids the environmental lobby’s inevitable shrieks of outrage. The result is that Western scientific and technical efforts have failed to develop new, cost-effective rare earth substitutes. Many universities no longer offer courses and advanced degrees in ‘materials science’, ‘metallurgy’, or ‘mining engineering’. China has cornered the market. Rare earths are now an ace in Beijing’s hand. ‘The geopolitical and economic importance of rare-earth minerals is vastly inflated by China’s overwhelming near-monopoly on the mining of these elements,’ says Ole Hansen, the head of commodities at Saxo Bank (

The result is that Western scientific and technical efforts have failed to develop new, cost-effective rare earth substitutes. Many universities no longer offer courses and advanced degrees in ‘materials science’, ‘metallurgy’, or ‘mining engineering’. China has cornered the market. Rare earths are now an ace in Beijing’s hand. ‘The geopolitical and economic importance of rare-earth minerals is vastly inflated by China’s overwhelming near-monopoly on the mining of these elements,’ says Ole Hansen, the head of commodities at Saxo Bank ( The Chinese are well aware of the importance of these commodities. In May 2019, Chinese leader Xi Jinping made a dramatic and highly symbolic gesture. He visited one of China’s most important rare-earth metals mining and processing plants, in Ganzhou, along with Liu He, his US chief negotiator in the trade talks.

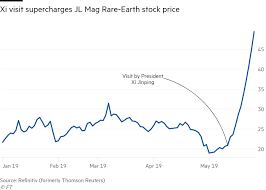

The Chinese are well aware of the importance of these commodities. In May 2019, Chinese leader Xi Jinping made a dramatic and highly symbolic gesture. He visited one of China’s most important rare-earth metals mining and processing plants, in Ganzhou, along with Liu He, his US chief negotiator in the trade talks. Even more significantly, he combined the visit with a stop at the monument in Yudu that marks the start of Mao’s ‘Long March’ during the Chinese civil war during the 1930s. The Long March, when the communist armies undertook a 6000-mile trek to the mountains of the north during the civil war, was a key event in communist China’s history. Xi was signalling a symbolic warning to America and the West that in any trade war, China is ready for a long, painful economic conflict.

Even more significantly, he combined the visit with a stop at the monument in Yudu that marks the start of Mao’s ‘Long March’ during the Chinese civil war during the 1930s. The Long March, when the communist armies undertook a 6000-mile trek to the mountains of the north during the civil war, was a key event in communist China’s history. Xi was signalling a symbolic warning to America and the West that in any trade war, China is ready for a long, painful economic conflict. The global effects of the visit to the Ganzhou plant were swift. Rare-earth equities leapt in value. America’s Blue Line Corporation of Texas rushed to sign a deal with Australia’s Lynas Corporation, one of the few rare-earths processors outside China. ‘I would expect US importers to develop local, domestic processing facilities over time and also to buy from non-China sources,’ said a spokesman.

The global effects of the visit to the Ganzhou plant were swift. Rare-earth equities leapt in value. America’s Blue Line Corporation of Texas rushed to sign a deal with Australia’s Lynas Corporation, one of the few rare-earths processors outside China. ‘I would expect US importers to develop local, domestic processing facilities over time and also to buy from non-China sources,’ said a spokesman. One hundred years ago, one of the most important conferences in the 20th century began (on 28 June 1919) culminating in the negotiation of a portentous document (finalised on 10 January 1920) that has had ramifications ever since. The Treaty of Versailles – signed to put a formal end to Word War I – turned out to be a disastrous script offering nothing but grief. It would lead in future decades to the death of millions and the chaos of the world in which we continue to live today.

One hundred years ago, one of the most important conferences in the 20th century began (on 28 June 1919) culminating in the negotiation of a portentous document (finalised on 10 January 1920) that has had ramifications ever since. The Treaty of Versailles – signed to put a formal end to Word War I – turned out to be a disastrous script offering nothing but grief. It would lead in future decades to the death of millions and the chaos of the world in which we continue to live today.

Meanwhile the peacemakers turned their attention to creating a new and supposedly more peaceful Europe. New countries sprang up in the Balkans, where the war had started in 1914. Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria and Greece all got new borders. The Slavs got a national home in Yugoslavia and an independent Poland was created with a curious corridor to Danzig on the Baltic, isolating East Prussia, and creating a serious international hostage to fortune. The Baltic states of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia suddenly appeared. Italy’s frontiers took in former Austrian territories inhabited by Italians. Ottoman Turkey lost everything as their empire was parcelled out. Further east the French got Syria – much to TE Lawrence and the Arabs’ dismay – and the British got the oil in what was now Iraq and Persia. (Kurdistan was completely overlooked, because Lloyd George had never heard of it and didn’t know where it was.)

Meanwhile the peacemakers turned their attention to creating a new and supposedly more peaceful Europe. New countries sprang up in the Balkans, where the war had started in 1914. Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria and Greece all got new borders. The Slavs got a national home in Yugoslavia and an independent Poland was created with a curious corridor to Danzig on the Baltic, isolating East Prussia, and creating a serious international hostage to fortune. The Baltic states of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia suddenly appeared. Italy’s frontiers took in former Austrian territories inhabited by Italians. Ottoman Turkey lost everything as their empire was parcelled out. Further east the French got Syria – much to TE Lawrence and the Arabs’ dismay – and the British got the oil in what was now Iraq and Persia. (Kurdistan was completely overlooked, because Lloyd George had never heard of it and didn’t know where it was.) When the details of the treaty were published in June 1919 German reaction was surprised and outraged. The still-blockaded German government was given just three weeks to accept the terms of the treaty, take it or leave it. Its immediate response was a

When the details of the treaty were published in June 1919 German reaction was surprised and outraged. The still-blockaded German government was given just three weeks to accept the terms of the treaty, take it or leave it. Its immediate response was a  On 28 June 1919, in a glittering ceremony in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles, the Peace Treaty to end World War I was finally signed. Next day Paris rejoiced, en fête; but in Germany the flags were at half mast.

On 28 June 1919, in a glittering ceremony in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles, the Peace Treaty to end World War I was finally signed. Next day Paris rejoiced, en fête; but in Germany the flags were at half mast.