The row that has blown up over the leaking of the British ambassador’s private opinions of President Trump and his administration has far-reaching consequences.

The row that has blown up over the leaking of the British ambassador’s private opinions of President Trump and his administration has far-reaching consequences.

In a crude but accurate of an ambassador’s job description, Sir Christopher Meyer in his memoir, DC Confidential, revealed that Tony Blair’s chief of staff had instructed him to ‘get up the arse of the White House and stay there’ when George W Bush was President. Having been effectively barred from the White House, suddenly finding himself with little or no access to Washington’s movers and shakers, Sir Kim Darroch had little choice but to fall on his sword.

Back in London a hunt is now on to find the leaker of those secret ‘diptels’; there have even been calls for the newspaper that published them to be charged under the Official Secrets Act. This is explosive stuff because the ‘freedom of the press’ is one of the cornerstones of a free society.

Freedom of the press is the right to circulate opinions in print without censorship by the government. Americans enjoy freedom of the press under the First Amendment to the US Constitution, which states:

‘Congress shall make no law… abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press…’

In the late 1770s this was remarkable stuff. Across the Atlantic, radical MP and journalist John Wilkes landed in jail for daring to criticise the London establishment in the press.

In the late 1770s this was remarkable stuff. Across the Atlantic, radical MP and journalist John Wilkes landed in jail for daring to criticise the London establishment in the press.

Wilkes was accused of treason and seditious libel for publishing articles critical of King George III’s government. He was arrested, thrown out of Parliament and put into prison. His legal travails, his publications, and his every movement were covered with great interest by the colonial newspapers. To those breakaway Britons, he provided a powerful example of why liberty of the press was so critical: after their observations of London’s heavy hand, they saw press freedom as vital for their new American state.

However, this declaration of press freedom caused concern, even in the new USA. For example, under the existing Common Law, protection against false allegations of defamation was a long standing legal right. How did that square with a press that had the legal right to print whatever it liked? ‘Fake news’ is no modern phenomenon.

Early American courts struggled with the argument that the punishment of ‘dangerous or offensive writings… [was] necessary for the preservation of peace and good order…’ How did that balance with a free press guaranteed by federal law? That difficult question was swept under the carpet for two centuries after the ratification of the First Amendment to the US Constitution.

Early American courts struggled with the argument that the punishment of ‘dangerous or offensive writings… [was] necessary for the preservation of peace and good order…’ How did that balance with a free press guaranteed by federal law? That difficult question was swept under the carpet for two centuries after the ratification of the First Amendment to the US Constitution.

Not so in Britain, however. In the early years of the 20th century spy fever gripped Britain. An Anglo-German naval arms race bred a panicky – if totally inaccurate – belief that the country was riddled with spies bent on uncovering the defence secrets of British dreadnoughts and dockyards. A worried government rushed through an Official Secrets Act in 1911 with little debate or opposition. The new Act had extremely wide-ranging powers. There were two main sections: Section 1 contained tough provisions against espionage and concentrated on the theft of military secrets; Section 2 dealt with unauthorised disclosure of government information, making it a criminal offence to disclose any official information without lawful authority.

The absurdity of making publication of even a Buckingham Palace menu a crime was quickly spotted by lawyers and widely ignored.

Across the Atlantic this problem came to light during World War I. In a famous case a man called Schenk had been convicted under the US wartime Espionage Act for publishing leaflets urging resistance to the Draft. This went against the right to freedom of speech protected by the First Amendment.

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes tried to unscramble the contradiction, ruling: ‘the question in every case is whether the words are used… to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent.’ He went on to add the all-important interpretation of the legal principle:

‘There is no threat to national security implied in the release of this material. It is embarrassing… but it is the duty of media organisations to bring new and interesting facts into the public domain. That is what they are there for. A prosecution on this basis would amount to an infringement on press freedom.’

The Supreme Court agreed, and held that virtually all forms of restraint on free speech were unconstitutional. The key was that embarrassing the government was no crime; the real illegality was the theft of secrets.

The Supreme Court agreed, and held that virtually all forms of restraint on free speech were unconstitutional. The key was that embarrassing the government was no crime; the real illegality was the theft of secrets.

Into this delicate legal minefield one of Britain’s most senior police officers has now blundered. Assistant Commissioner Neil Basu said the leak had caused damage to the UK’s international relations, pompously warning that journalists who publish leaked information risk going to jail. Senior legal figures said that Basu, the head of the Metropolitan Police’s specialist operations, appeared to have set out to ‘protect the Government from embarrassment’ after he issued his warning that the publication of the leaked memos could in itself be ‘a criminal matter’.

The subsequent outrage was both unnecessary and predictable. Sharp-eyed lawyers immediately pointed out that in law, the authorities have to prove that ‘damage’ – not mere embarrassment – has been caused to Britain’s international relations through a leak.

However, nothing that Ambassador Darroch said in his diptels was remarkable. He could have been quoting the views of the Guardian or the New York Times on Trump. Nothing has been published that in any way affects national security. So for the Mail to be threatened with the Official Secrets Act 1989 was a clumsy and unwise thing to do. The real crime is the theft and leaking of the secret diptels. Even then the case is arguable: nothing that has been leaked in these particular diplomatic reports threatens Britain’s (or Britons’) security. However, even if there had been sensitive material involved, it is a decision for responsible newspaper editors to decide whether or not they should publish it.

The authorities quickly realised that a PR disaster was looming; from 10 Downing Street downwards the hapless Assistant Chief Commissioner of the Met was thrown under the bus, ethnic figurehead of ‘diversity’ and Common Purpose mole or not. Even London Mayor, Sadiq Khan, who is responsible for policing in London, said the media ‘must not be told’ what they could publish. Sir Paul Stephenson, a former Metropolitan Police Commissioner, and a mentor to Mr Basu when he was at the force, warned that the police must ‘step very carefully and warily’.

Politicians en masse quickly backed away from what was an obvious tar baby; trying to muzzle – let alone jail – newspaper editors in today’s digital communications world would be political suicide, especially when no lives are at risk from the disclosure.

Here is the key: whereas Julian Assange and his unwitting pawn Private Chelsea Manning stole US military secrets and really did put many undercover lives at risk via Wikileaks, nothing the Mail has published risks anything other than the red faces of officials. So, to threaten editors with the OSA and Court Number One at the Old Bailey was a blunder of monumental proportions.

The irony is that the British press are often far too ‘responsible’. For example, over the Rochdale sex gangs and the Elm Guest House MPs paedophile scandals the press kept too quiet whilst great wrongs continued. They knew all about the Pakistani sex traffickers and they knew all about the behaviour of MPs Cyril Smith and Nicholas Fairbairn; but, under pressure not to rock the political or policing boat, the press stayed quiet. Too quiet, too long.

The irony is that the British press are often far too ‘responsible’. For example, over the Rochdale sex gangs and the Elm Guest House MPs paedophile scandals the press kept too quiet whilst great wrongs continued. They knew all about the Pakistani sex traffickers and they knew all about the behaviour of MPs Cyril Smith and Nicholas Fairbairn; but, under pressure not to rock the political or policing boat, the press stayed quiet. Too quiet, too long.

Press freedom is today a delicate balancing act, requiring skilful tightrope walking by editors and journalists. The threats and heavy hand of Mr Plod would be funny – if it were not so serious.

‘Peace at home; peace in the world.’ Atatürk’s homely ambition has never been more important for Turkey. However, a number of crises are coming together inexorably to force Ankara to think long and hard about its future intentions. Turkey is at a major crossroads.

‘Peace at home; peace in the world.’ Atatürk’s homely ambition has never been more important for Turkey. However, a number of crises are coming together inexorably to force Ankara to think long and hard about its future intentions. Turkey is at a major crossroads. Then, in late June 2019 (in the margins of the G20 Osaka meeting), the Turkish president claimed that a deal had been struck. President Trump had told him there would be no sanctions over the Russian deal and that Turkey had been had been ‘treated unfairly’ over the move.

Then, in late June 2019 (in the margins of the G20 Osaka meeting), the Turkish president claimed that a deal had been struck. President Trump had told him there would be no sanctions over the Russian deal and that Turkey had been had been ‘treated unfairly’ over the move. The problem is that Turkey and Russia have serious form going back to the days of the Tsars. For example, the Crimean War in the 1850s was really all about Russian and Turkish rivalry. Since the days of the Ottoman Empire, Turkey has always sought to deny Russia a significant presence to the south or in the eastern Mediterranean. But that is now where Russia is becoming increasingly active – especially in Syria. As Russian influence grows, Turkey’s room for regional influence shrinks. Turkey’s recent accommodation of Russia is therefore historically and geopolitically unusual.

The problem is that Turkey and Russia have serious form going back to the days of the Tsars. For example, the Crimean War in the 1850s was really all about Russian and Turkish rivalry. Since the days of the Ottoman Empire, Turkey has always sought to deny Russia a significant presence to the south or in the eastern Mediterranean. But that is now where Russia is becoming increasingly active – especially in Syria. As Russian influence grows, Turkey’s room for regional influence shrinks. Turkey’s recent accommodation of Russia is therefore historically and geopolitically unusual. Right! Hands up all those who have heard of rare earths?

Right! Hands up all those who have heard of rare earths? Scandium Found in aerospace alloys and cars’ headlamps

Scandium Found in aerospace alloys and cars’ headlamps So, just as with plastic, the West has ducked responsibility, outsourcing the environmental challenges of rare earths by dumping the problem out in the dusty deserts and cheap mass labour of far-distant China. By doing so it has allowed Beijing to corner the global market. There’s a price; China holds 37 per cent of the world’s rare-earth deposits and it controls the rest. Even when rare earths are mined in the US – or in other nations, such as Estonia – the extracted material is sent to China for processing. It’s cheaper, easier and, most important, it avoids the environmental lobby’s inevitable shrieks of outrage.

So, just as with plastic, the West has ducked responsibility, outsourcing the environmental challenges of rare earths by dumping the problem out in the dusty deserts and cheap mass labour of far-distant China. By doing so it has allowed Beijing to corner the global market. There’s a price; China holds 37 per cent of the world’s rare-earth deposits and it controls the rest. Even when rare earths are mined in the US – or in other nations, such as Estonia – the extracted material is sent to China for processing. It’s cheaper, easier and, most important, it avoids the environmental lobby’s inevitable shrieks of outrage. The result is that Western scientific and technical efforts have failed to develop new, cost-effective rare earth substitutes. Many universities no longer offer courses and advanced degrees in ‘materials science’, ‘metallurgy’, or ‘mining engineering’. China has cornered the market. Rare earths are now an ace in Beijing’s hand. ‘The geopolitical and economic importance of rare-earth minerals is vastly inflated by China’s overwhelming near-monopoly on the mining of these elements,’ says Ole Hansen, the head of commodities at Saxo Bank (

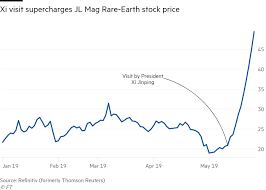

The result is that Western scientific and technical efforts have failed to develop new, cost-effective rare earth substitutes. Many universities no longer offer courses and advanced degrees in ‘materials science’, ‘metallurgy’, or ‘mining engineering’. China has cornered the market. Rare earths are now an ace in Beijing’s hand. ‘The geopolitical and economic importance of rare-earth minerals is vastly inflated by China’s overwhelming near-monopoly on the mining of these elements,’ says Ole Hansen, the head of commodities at Saxo Bank ( The Chinese are well aware of the importance of these commodities. In May 2019, Chinese leader Xi Jinping made a dramatic and highly symbolic gesture. He visited one of China’s most important rare-earth metals mining and processing plants, in Ganzhou, along with Liu He, his US chief negotiator in the trade talks.

The Chinese are well aware of the importance of these commodities. In May 2019, Chinese leader Xi Jinping made a dramatic and highly symbolic gesture. He visited one of China’s most important rare-earth metals mining and processing plants, in Ganzhou, along with Liu He, his US chief negotiator in the trade talks. Even more significantly, he combined the visit with a stop at the monument in Yudu that marks the start of Mao’s ‘Long March’ during the Chinese civil war during the 1930s. The Long March, when the communist armies undertook a 6000-mile trek to the mountains of the north during the civil war, was a key event in communist China’s history. Xi was signalling a symbolic warning to America and the West that in any trade war, China is ready for a long, painful economic conflict.

Even more significantly, he combined the visit with a stop at the monument in Yudu that marks the start of Mao’s ‘Long March’ during the Chinese civil war during the 1930s. The Long March, when the communist armies undertook a 6000-mile trek to the mountains of the north during the civil war, was a key event in communist China’s history. Xi was signalling a symbolic warning to America and the West that in any trade war, China is ready for a long, painful economic conflict. The global effects of the visit to the Ganzhou plant were swift. Rare-earth equities leapt in value. America’s Blue Line Corporation of Texas rushed to sign a deal with Australia’s Lynas Corporation, one of the few rare-earths processors outside China. ‘I would expect US importers to develop local, domestic processing facilities over time and also to buy from non-China sources,’ said a spokesman.

The global effects of the visit to the Ganzhou plant were swift. Rare-earth equities leapt in value. America’s Blue Line Corporation of Texas rushed to sign a deal with Australia’s Lynas Corporation, one of the few rare-earths processors outside China. ‘I would expect US importers to develop local, domestic processing facilities over time and also to buy from non-China sources,’ said a spokesman. One hundred years ago, one of the most important conferences in the 20th century began (on 28 June 1919) culminating in the negotiation of a portentous document (finalised on 10 January 1920) that has had ramifications ever since. The Treaty of Versailles – signed to put a formal end to Word War I – turned out to be a disastrous script offering nothing but grief. It would lead in future decades to the death of millions and the chaos of the world in which we continue to live today.

One hundred years ago, one of the most important conferences in the 20th century began (on 28 June 1919) culminating in the negotiation of a portentous document (finalised on 10 January 1920) that has had ramifications ever since. The Treaty of Versailles – signed to put a formal end to Word War I – turned out to be a disastrous script offering nothing but grief. It would lead in future decades to the death of millions and the chaos of the world in which we continue to live today.

Meanwhile the peacemakers turned their attention to creating a new and supposedly more peaceful Europe. New countries sprang up in the Balkans, where the war had started in 1914. Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria and Greece all got new borders. The Slavs got a national home in Yugoslavia and an independent Poland was created with a curious corridor to Danzig on the Baltic, isolating East Prussia, and creating a serious international hostage to fortune. The Baltic states of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia suddenly appeared. Italy’s frontiers took in former Austrian territories inhabited by Italians. Ottoman Turkey lost everything as their empire was parcelled out. Further east the French got Syria – much to TE Lawrence and the Arabs’ dismay – and the British got the oil in what was now Iraq and Persia. (Kurdistan was completely overlooked, because Lloyd George had never heard of it and didn’t know where it was.)

Meanwhile the peacemakers turned their attention to creating a new and supposedly more peaceful Europe. New countries sprang up in the Balkans, where the war had started in 1914. Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria and Greece all got new borders. The Slavs got a national home in Yugoslavia and an independent Poland was created with a curious corridor to Danzig on the Baltic, isolating East Prussia, and creating a serious international hostage to fortune. The Baltic states of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia suddenly appeared. Italy’s frontiers took in former Austrian territories inhabited by Italians. Ottoman Turkey lost everything as their empire was parcelled out. Further east the French got Syria – much to TE Lawrence and the Arabs’ dismay – and the British got the oil in what was now Iraq and Persia. (Kurdistan was completely overlooked, because Lloyd George had never heard of it and didn’t know where it was.) When the details of the treaty were published in June 1919 German reaction was surprised and outraged. The still-blockaded German government was given just three weeks to accept the terms of the treaty, take it or leave it. Its immediate response was a

When the details of the treaty were published in June 1919 German reaction was surprised and outraged. The still-blockaded German government was given just three weeks to accept the terms of the treaty, take it or leave it. Its immediate response was a  On 28 June 1919, in a glittering ceremony in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles, the Peace Treaty to end World War I was finally signed. Next day Paris rejoiced, en fête; but in Germany the flags were at half mast.

On 28 June 1919, in a glittering ceremony in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles, the Peace Treaty to end World War I was finally signed. Next day Paris rejoiced, en fête; but in Germany the flags were at half mast. The invasion of Normandy by Allied forces on 6 June 1944, was the Western Allies’ most critical operation of World War II.

The invasion of Normandy by Allied forces on 6 June 1944, was the Western Allies’ most critical operation of World War II. The 50 miles of Normandy coastline is therefore one of the most important battlefields of World War II. Today’s golden tourist beaches witnessed the start of one the most ambitious and historically important campaigns in human history. In its strategy and scope – and with its enormous stakes for the future of the free world – it was among the greatest military achievements ever. The Western Allies’ goal was simple and clear cut: to put an end to the Germany military machine and topple Adolf Hitler’s barbarous Nazi regime.

The 50 miles of Normandy coastline is therefore one of the most important battlefields of World War II. Today’s golden tourist beaches witnessed the start of one the most ambitious and historically important campaigns in human history. In its strategy and scope – and with its enormous stakes for the future of the free world – it was among the greatest military achievements ever. The Western Allies’ goal was simple and clear cut: to put an end to the Germany military machine and topple Adolf Hitler’s barbarous Nazi regime. For the very old men of the surviving British, American and Canadian troops who spearheaded that assault at dawn on what one commentator called ‘the longest day’, this year’s anniversary was special. It will be their last big celebration of their victory, 75 years ago in the summer of 1944. Amid the beautiful French holiday countryside, one of the most critical struggles of the twentieth century took place. It was a struggle that would eventually end at the gates of Hitler’s Chancellery in Berlin on the last day of April 1945, as a demented and broken Hitler poisoned his dog and his mistress, before finally blowing his own brains out.

For the very old men of the surviving British, American and Canadian troops who spearheaded that assault at dawn on what one commentator called ‘the longest day’, this year’s anniversary was special. It will be their last big celebration of their victory, 75 years ago in the summer of 1944. Amid the beautiful French holiday countryside, one of the most critical struggles of the twentieth century took place. It was a struggle that would eventually end at the gates of Hitler’s Chancellery in Berlin on the last day of April 1945, as a demented and broken Hitler poisoned his dog and his mistress, before finally blowing his own brains out. ‘Ike’ had 3 million troops under his command; what they all devoured in just one day was stupendous. According to historian Rick Atkinson, US commanders had ‘calculated daily combat consumption, from fuel to bullets to chewing gum, at 41,298 pounds per soldier. Sixty million K-rations, enough to feed the invaders for a month, were packed in 500-ton bales.’

‘Ike’ had 3 million troops under his command; what they all devoured in just one day was stupendous. According to historian Rick Atkinson, US commanders had ‘calculated daily combat consumption, from fuel to bullets to chewing gum, at 41,298 pounds per soldier. Sixty million K-rations, enough to feed the invaders for a month, were packed in 500-ton bales.’ Here we go again. Even as you read this, the war drums are beating. And – surprise, surprise – it’s Iran that’s at the heart of this latest eruption of trouble in the Middle East.

Here we go again. Even as you read this, the war drums are beating. And – surprise, surprise – it’s Iran that’s at the heart of this latest eruption of trouble in the Middle East. The 1979 revolution created strong passions in both countries. In Iran it was a glow of triumphalism over ‘The Great Satan’; and in the USA a simmering resentment at what was seen as a national humiliation. Few episodes in living memory, other than the sight of Royal Marines surrendering to Argentine invaders in 1982, show how public emotion can drive political decisions.

The 1979 revolution created strong passions in both countries. In Iran it was a glow of triumphalism over ‘The Great Satan’; and in the USA a simmering resentment at what was seen as a national humiliation. Few episodes in living memory, other than the sight of Royal Marines surrendering to Argentine invaders in 1982, show how public emotion can drive political decisions. Satellites report Iran moving S-300 SAMs and massing armed fast gunboats in the Gulf. Their role would be to swarm out and attack American and Western shipping in the Strait of Hormuz, through which much of the world’s oil supplies pass.

Satellites report Iran moving S-300 SAMs and massing armed fast gunboats in the Gulf. Their role would be to swarm out and attack American and Western shipping in the Strait of Hormuz, through which much of the world’s oil supplies pass. In response to these rising tensions, Washington has upped the ante, flying B-52 bombers into the region and moving a nuclear equipped carrier task force with 80 aircraft, accompanied by a Marine Expeditionary Force, to the Gulf. The objective of the exercise, in the words of national security adviser, is to ‘send a message’ to Iran. Donald Trump’s tweet spells out the threat implicitly: ‘If Iran wants to fight, that will be the official end of Iran.’

In response to these rising tensions, Washington has upped the ante, flying B-52 bombers into the region and moving a nuclear equipped carrier task force with 80 aircraft, accompanied by a Marine Expeditionary Force, to the Gulf. The objective of the exercise, in the words of national security adviser, is to ‘send a message’ to Iran. Donald Trump’s tweet spells out the threat implicitly: ‘If Iran wants to fight, that will be the official end of Iran.’ Tehran has significantly expanded its footprint over the past decade, making powerful allies across the Middle East as it forges its ‘Land Bridge’ west to the Mediterranean. The IRGC’s Quds Force controls up to 140,000 Shia fighters across Syria, many dug in on Israel’s border. Quds has close links to Hezbollah, Lebanon’s well-armed anti-Israel military organisation, part of Iran’s ‘axis of resistance’, armed groups with tens of thousands of Shi’ite Muslim fighters backing Tehran. In Gaza, Iran supports Palestinian Islamic Jihad in its struggle against what Tehran calls the ‘Zionist enemy’. Further south in Yemen, the insurrectionary Houthi rebels are openly fighting Iran’s enemy, Saudi Arabia.

Tehran has significantly expanded its footprint over the past decade, making powerful allies across the Middle East as it forges its ‘Land Bridge’ west to the Mediterranean. The IRGC’s Quds Force controls up to 140,000 Shia fighters across Syria, many dug in on Israel’s border. Quds has close links to Hezbollah, Lebanon’s well-armed anti-Israel military organisation, part of Iran’s ‘axis of resistance’, armed groups with tens of thousands of Shi’ite Muslim fighters backing Tehran. In Gaza, Iran supports Palestinian Islamic Jihad in its struggle against what Tehran calls the ‘Zionist enemy’. Further south in Yemen, the insurrectionary Houthi rebels are openly fighting Iran’s enemy, Saudi Arabia. Just like the tip-off which led to the

Just like the tip-off which led to the  There is no doubt that Huawei has serious form over collecting secret intelligence and mis-using its computer hardware.

There is no doubt that Huawei has serious form over collecting secret intelligence and mis-using its computer hardware. Worse, Huawei works directly for the Chinese government. Last December their Chief Financial Officer,

Worse, Huawei works directly for the Chinese government. Last December their Chief Financial Officer,  The USA means business. The

The USA means business. The  The

The  Europe faces a major problem with its restive Muslim population. Like it or not, we seem to be in the middle of a war with echoes of the religious wars of the Crusades and the bloody strife between Protestants and Catholics that tore Europe apart between 1550 and 1650.

Europe faces a major problem with its restive Muslim population. Like it or not, we seem to be in the middle of a war with echoes of the religious wars of the Crusades and the bloody strife between Protestants and Catholics that tore Europe apart between 1550 and 1650. The fire at Notre-Dame is actually part of a clear pattern of attacks. Three years ago a ‘commando unit’ of jihadis tried to destroy the cathedral by detonating cylinders of natural gas. Three days before the Notre-Dame fire, Ines Madani (a convert to Islam) was sentenced to eight years in prison for recruiting a French ISIS terrorist group. The Notre-Dame fire also occurred during a period in which 800 churches have been attacked in France in 2018.

The fire at Notre-Dame is actually part of a clear pattern of attacks. Three years ago a ‘commando unit’ of jihadis tried to destroy the cathedral by detonating cylinders of natural gas. Three days before the Notre-Dame fire, Ines Madani (a convert to Islam) was sentenced to eight years in prison for recruiting a French ISIS terrorist group. The Notre-Dame fire also occurred during a period in which 800 churches have been attacked in France in 2018. If the Notre-Dame fire really was an accident, there is no explanation of how it started. Benjamin Mouton, Notre-Dame’s former chief architect, pointed out that no electric cable or appliance, and no source of heat, could be placed in the attic – by law. However, the fire spread so quickly that the firefighters who rushed to the spot as soon as they could were shocked. Remi Fromont, architect of the French Historical Monuments said: ‘That fire could not start from any element present where it started. A major heat source is necessary to launch such a disaster.’

If the Notre-Dame fire really was an accident, there is no explanation of how it started. Benjamin Mouton, Notre-Dame’s former chief architect, pointed out that no electric cable or appliance, and no source of heat, could be placed in the attic – by law. However, the fire spread so quickly that the firefighters who rushed to the spot as soon as they could were shocked. Remi Fromont, architect of the French Historical Monuments said: ‘That fire could not start from any element present where it started. A major heat source is necessary to launch such a disaster.’ The only constant in life is change. If anything proves the truth of this saying, it is British politics. Although many regard the recent chaotic shambles, barefaced lies and back-stabbing intrigue of Brexit as a sure sign of the weakness of the British political system, it is not. It is a shambolic yet important example of the very real strengths of Britain’s unwritten constitution.

The only constant in life is change. If anything proves the truth of this saying, it is British politics. Although many regard the recent chaotic shambles, barefaced lies and back-stabbing intrigue of Brexit as a sure sign of the weakness of the British political system, it is not. It is a shambolic yet important example of the very real strengths of Britain’s unwritten constitution. For example, what exactly did the famous Founding Fathers of the United States of America come up with 232 years ago in their famous 1787 written Constitution on contentious subjects like abortion, slavery and the latest – the 27th Amendment – which prohibits laws on ‘delaying new Congressional salaries from taking effect until after the next election of Congress’? In the British context, would MPs’ salaries really require an amendment to a national constitution?

For example, what exactly did the famous Founding Fathers of the United States of America come up with 232 years ago in their famous 1787 written Constitution on contentious subjects like abortion, slavery and the latest – the 27th Amendment – which prohibits laws on ‘delaying new Congressional salaries from taking effect until after the next election of Congress’? In the British context, would MPs’ salaries really require an amendment to a national constitution? The ‘Glorious Revolution’ of 1688, when Parliament kicked out the last Stuart King and invited a foreigner to reign, can be seen as the root of today’s modern constitution. The 1689 Bill of Rights is still the bedrock, even today, of the UK’s constitutional arrangements. That Act settled the primacy of Parliament over the monarch, providing for the regular meeting of Parliament, free elections to the Commons, free speech in parliamentary debates, and some basic human rights, such as freedom from ‘cruel or unusual punishment’. It also sets out the need for ‘the Crown’ to seek the consent of the people, ‘as represented in Parliament’.

The ‘Glorious Revolution’ of 1688, when Parliament kicked out the last Stuart King and invited a foreigner to reign, can be seen as the root of today’s modern constitution. The 1689 Bill of Rights is still the bedrock, even today, of the UK’s constitutional arrangements. That Act settled the primacy of Parliament over the monarch, providing for the regular meeting of Parliament, free elections to the Commons, free speech in parliamentary debates, and some basic human rights, such as freedom from ‘cruel or unusual punishment’. It also sets out the need for ‘the Crown’ to seek the consent of the people, ‘as represented in Parliament’. If we go back to 1911 there is an earlier revolutionary change in British politics, which was swiftly resolved by an unwritten constitution enshrined in laws. When the House of Lords’ rejected Chancellor of the Exchequer, David Lloyd George’s ‘

If we go back to 1911 there is an earlier revolutionary change in British politics, which was swiftly resolved by an unwritten constitution enshrined in laws. When the House of Lords’ rejected Chancellor of the Exchequer, David Lloyd George’s ‘ Like many others, I was surprised by the announcement by Air Chief Marshal Sir Stephen Hillier, Chief of the Air Staff, that his Reaper drone crews will be eligible for the new Operational Service Medal for their contribution to the war in Syria and the defeat of ISIS (also known as Daesh). Traditionally, medals have always been awarded based on risk and rigour. It may seem a reasonable assumption that there is not much risk sitting in a nice warm office up at RAF Waddington in Lincolnshire where they operate their Unmanned Air Vehicles (UAVs). More like playing computer games, perhaps? Where is the risk and rigour in that?

Like many others, I was surprised by the announcement by Air Chief Marshal Sir Stephen Hillier, Chief of the Air Staff, that his Reaper drone crews will be eligible for the new Operational Service Medal for their contribution to the war in Syria and the defeat of ISIS (also known as Daesh). Traditionally, medals have always been awarded based on risk and rigour. It may seem a reasonable assumption that there is not much risk sitting in a nice warm office up at RAF Waddington in Lincolnshire where they operate their Unmanned Air Vehicles (UAVs). More like playing computer games, perhaps? Where is the risk and rigour in that? During the campaign to destroy the extremists in Iraq and Syria, drones were used to carry out strikes, gather intelligence and conduct surveillance. While front-line operational aircrew do operations for maybe six months or a year at a time, drone operations staff face different challenges The Reaper force is on duty 24/7/365, monitoring an enemy that is elusive, dangerous and determined to attack the West in any way it can in pursuit of its twisted, fanatical world view. The personal strain and pressure watching the every move of these individuals is immense and unrelenting.

During the campaign to destroy the extremists in Iraq and Syria, drones were used to carry out strikes, gather intelligence and conduct surveillance. While front-line operational aircrew do operations for maybe six months or a year at a time, drone operations staff face different challenges The Reaper force is on duty 24/7/365, monitoring an enemy that is elusive, dangerous and determined to attack the West in any way it can in pursuit of its twisted, fanatical world view. The personal strain and pressure watching the every move of these individuals is immense and unrelenting. This insight into the combat stress of the new warfare is a reflection of how in the last decade drones have become a new battlefield in the ‘vertical flank’. As long ago as 2004, the militant group Hezbollah began to use ‘adapted commercially available hobby systems for combat roles’. These modified toys can be bought easily, as the Gatwick debacle in December 2018 demonstrated, and – at prices ranges from US $200 to $700 – they are as cheap as chips to the military.

This insight into the combat stress of the new warfare is a reflection of how in the last decade drones have become a new battlefield in the ‘vertical flank’. As long ago as 2004, the militant group Hezbollah began to use ‘adapted commercially available hobby systems for combat roles’. These modified toys can be bought easily, as the Gatwick debacle in December 2018 demonstrated, and – at prices ranges from US $200 to $700 – they are as cheap as chips to the military. ‘As drones become deadlier, stealthier, faster, smaller and cheaper, the nuisance and threat posed by them is expected to increase, ranging from national security to individual privacy,’ Grand View warns. ‘Keeping the above-mentioned threat in mind, there are significant efforts – both in terms of money and time – being invested in the development and manufacturing of anti-drone technologies.’ The Dutch have even trained eagles to attack drones.

‘As drones become deadlier, stealthier, faster, smaller and cheaper, the nuisance and threat posed by them is expected to increase, ranging from national security to individual privacy,’ Grand View warns. ‘Keeping the above-mentioned threat in mind, there are significant efforts – both in terms of money and time – being invested in the development and manufacturing of anti-drone technologies.’ The Dutch have even trained eagles to attack drones.